Technology

All mid-infrared detection products of NLIR technology are based on sum-frequency generation (SFG). SFG is a highly sophisticated nonlinear optical process where two photons annihilate in the creation of a new photon with the same energy as the sum of the originals.

Many know the special case of SFG called second-harmonic generation. That is used most widely in laser pointers to generate green light from a 1064 nm laser diode. In our products, we use SFG in a process called upconversion, which aims to change the wavelength of incoming mid-infrared (MIR) light to near-visible light.

Nonlinear optical processes are generally driven by high-intensity electrical fields inside media that exhibit large nonlinear coefficients and small losses, for example, LiNbO 3 crystals. For upconversion, in which three electrical fields participate, one of these fields must be of sufficiently high intensity. Although upconversion has been known for many years, the need for a high-intensity laser field has made it either too expensive or too inefficient for commercialization.

NLIR Technology

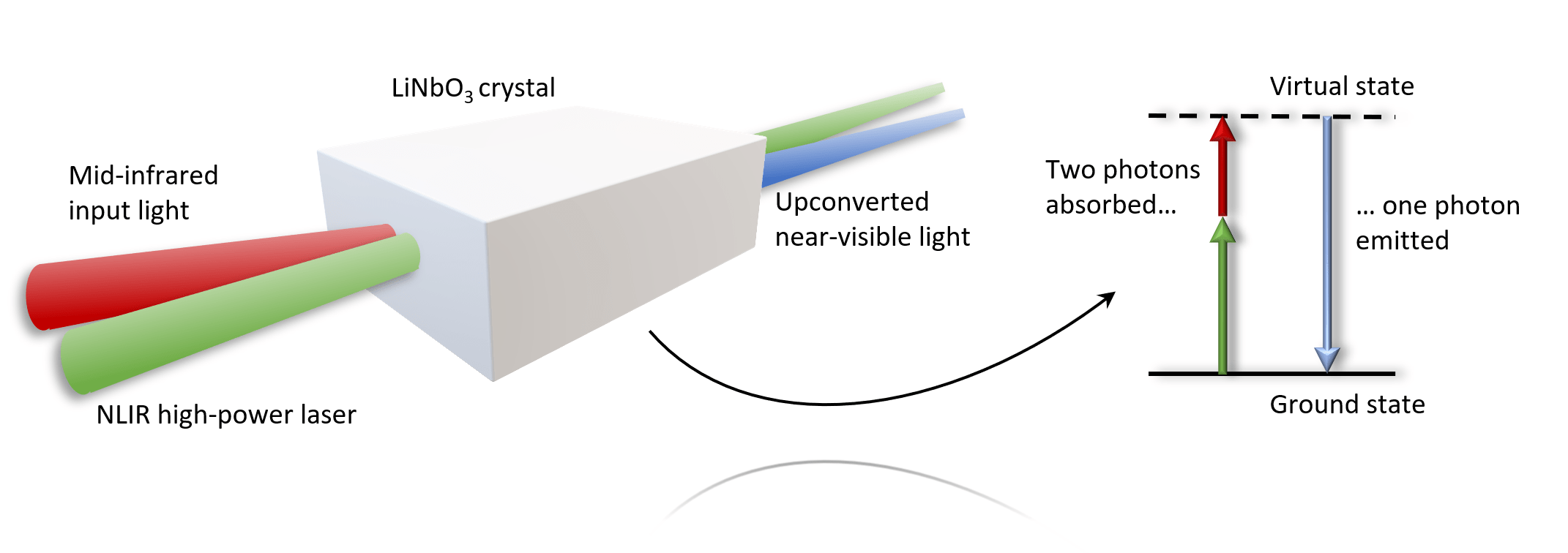

The core of NLIR technology is providing a high-intensity laser field (1064 nm,> 1 MW / cm 2 continuous wave) inside a crystal in a simple way that allows MIR light to enter and the generated near-visible light to exit without either being attenuated. The figure below illustrates a crystal with a high-power laser field (green) penetrating it, and a MIR signal coming in (red) overlapping with the high-power field. At the output, the upconverted beam (blue) can be separated from the high-power beam and measured with a near-visible light detector, for example, a Silicon-based CMOS array, an APD, or even a smartphone camera.

Upconversion Module Technology

The schematic indicated by the arrow illustrates energy conservation in the upconversion process. During the process one photon from the high-power laser field and one MIR photon combine and become one near-visible light photon; the length of the arrows signifies the energy and, hence, wavelength. The term “Virtual state” at the top of the diagram indicates that the photons are not absorbed to a physical state in the crystal (as is the case for electronic absorption) but only interact with bound electrons through electric forces.

After upconversion, the near-visible light can be detected with a detector suitable for the application in mind. That can be achieved with a CMOS array in a grating spectrometer (like the 2.0 – 5.0 µm Spectrometer in “Products”), or a very fast or sensitive point detector (like the Single-wavelength Detectors).

Noise

The products of NLIR have exceptional noise properties. Many sources of noise known from conventional MIR detectors are avoided but a new one is introduced during upconversion.

The requirements for upconversion, which limit the achievable efficiency and bandwidth, inherently filter out thermal noise from the surroundings. The only noise in the detectable bandwidth that co-propagates with the signal is upconverted and makes it to detection. The rest of the thermal noise from the surroundings that would be detected by a conventional MIR detector is simply not upconverted. Similarly, a conventional MIR detector also has a significant amount of internal noise because of its own temperature, which is the reason why many MIR detectors are cryo-cooled. This noise contribution is also largely avoided after upconversion because hardly any thermally emitted photons exist at the upconverted wavelengths at room temperature.

The upconversion process technology itself is perfectly noiseless. It has been shown in the literature that even on a quantum mechanical level, an upconverted photon is an exact copy of the longer-wavelength original except for the wavelength. This means that the upconversion process itself does not contribute to any noise in the detection scheme.

The two new sources of noise introduced in the upconversion scheme are significant enough to be observed in the 2.0 – 5.0 μm Spectrometers at sampling frequencies <0.1 Hz. In the Single-Wavelength Detectors, the contribution varies depending on wavelength and bandwidth, but its effect is always included in the specifications.

Speed

An important part of the physics behind upconversion is the time constant of the nonlinear interaction. A common misunderstanding among non-experts is that the conversion process happens at the speed of light. While it is true that light is not slowed down by other than a factor of the linear refractive index during the conversion process, the interaction itself has little to do with how fast light is moving. The time constant of the conversion process is determined by how fast the bound electrons in the material respond to the force of an applied electric field. Naturally, the electrons do not react infinitely fast, but their response is so rapid compared to all other dynamics involved that for (almost) any application, their response can be considered instantaneous. Hence, the upconversion process technology itself does not cause time lag or jitter.

However, it turns out (strictly speaking) that dispersion in the crystal in principle causes time blurring on very short time scales. In the most sensitive Single-Wavelength Detectors that NLIR manufactures, the effect will start becoming notable at modulation frequencies above 100 GHz. In the more broadband devices, it will be at even higher modulation frequencies. Consequently, none of the Single-Wavelength Detectors is affected by the dispersion-induced time blurring. The Spectrometers are only affected in terms of slightly reduced sensitivity for input pulses shorter than 100 fs; the measured spectrum is not affected.

Efficiency

The efficiency of the conversion process dependents on the power of the 1064 nm laser mentioned above. Largely, higher powers give higher conversion efficiencies. The size of the bandwidth in an upconversion process also has a significant impact on the efficiency. For the smallest bandwidths of around 50 nm, the conversion efficiency can reach up to 0.1, enabling extremely sensitive measurements. Meanwhile, wider simultaneous conversion such as 3.3 µm to 5.3 µm results in a conversion efficiency of approximately 0.005, and even wider conversion from 1.9 µm to 5.3 µm has a conversion efficiency of 0.0005. The ideal combination of bandwidth and conversion efficiency varies depending on many factors, but even the lower conversion efficiencies offer new possibilities for measuring, particularly in spectroscopic applications.

Discover our products based on Upconversion Module Technology